If economic freedom were a stock, analysts would call it boring — and then quietly recommend buying it anyway.

For decades, states that limit government growth, keep taxes low and predictable, and allow labor markets to adjust have outperformed their peers on jobs, incomes, and growth. This is not fashionable economics. It doesn’t promise quick fixes or dramatic announcements. It just works. And the latest Economic Freedom of North America (EFNA) data published by the Fraser Institute show that it still does.

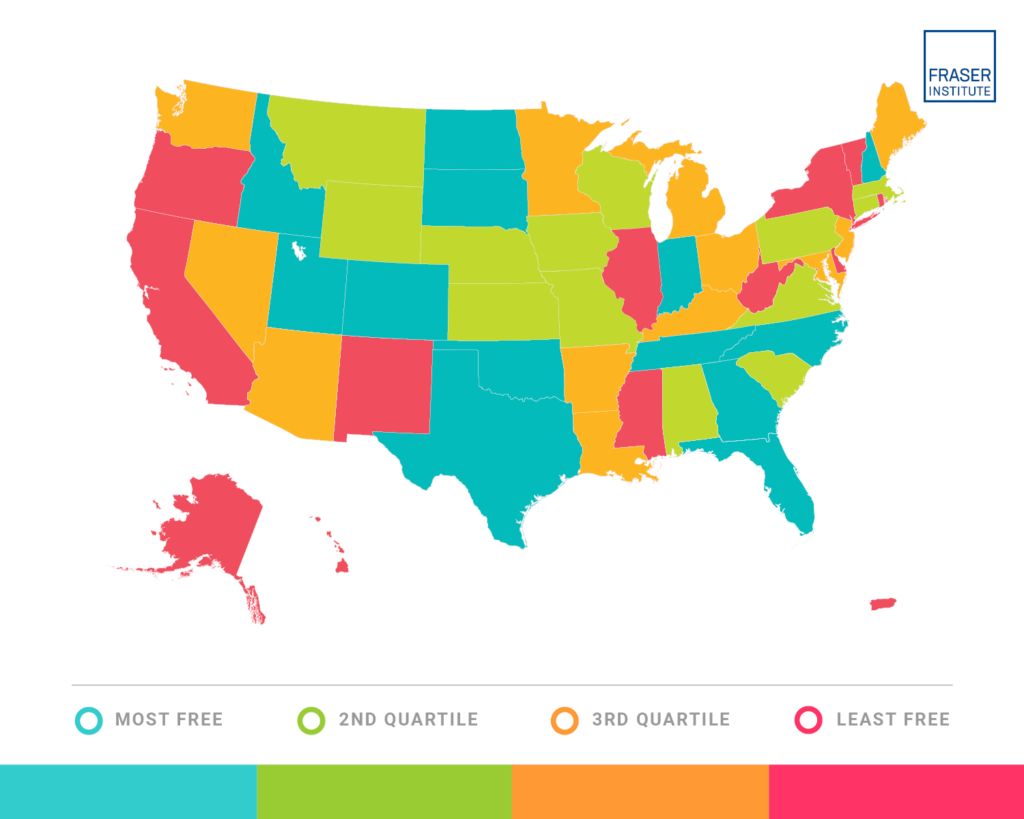

The EFNA index evaluates states using the latest data (2023) across three simple but powerful dimensions: how much the government spends relative to income, how heavy and complex taxes are, and how flexible labor markets remain. Nothing exotic. No ideological scoring. Just the institutional rules under which people live. Those rules matter because they shape incentives.

When government grows faster than the economy, something else must shrink. When taxes are steep or complex, labor and capital shift from production to avoidance. When labor rules make it harder for employers and employees to contract, hiring slows and labor markets soften.

None of this shows up overnight. But it shows up reliably. You can see it in how states behave — and how people respond.

One limitation is worth acknowledging. The EFNA index measures how heavy taxes are, but not yet how complex they are. Complexity matters because it raises compliance costs, increases uncertainty, and gives large firms an advantage over workers and small businesses.

The EFNA authors are considering ways to add complexity to the index. When added, complexity would likely reinforce the existing findings rather than overturn them.

The incentives measured by the EFNA index are clearly reflected in state outcomes. Take Vance’s home state of Texas, which ranks fourth nationally.

Texas didn’t become an economic magnet by offering clever incentives or chasing headlines. It did it by staying boring. No personal income tax. Relatively flexible labor markets. A business climate that allowed firms to expand without asking permission.

The result? More than two million net jobs added since 2019, and real output growth that has consistently beaten the national average.

But here’s the plot twist: Texas has stopped climbing in the rankings. Why?

Because state and local spending started growing faster than population growth and inflation, and property taxes quietly did the rest. The Texas model still works — but the state has begun to retreat from it.

Political economy matters here: it’s easy to defend low taxes while letting spending rise one budget at a time. The index catches that drift even when politics doesn’t.

Florida, ranked sixth, tells a similar story (with better weather and beaches).

No personal income tax and flexible labor markets have fueled population inflows, job creation, and strong GDP growth. People vote with their feet, and many are voting for Florida.

Yet Florida slipped slightly after years near the top. Not because it raised taxes, but because spending expanded rapidly during the boom. Growth makes this temptation worse. When revenues pour in, restraint feels unnecessary. The index is less forgiving. Growth can hide fiscal excess for a while. It cannot neutralize it.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/XZuhe/

Kansas, ranked fourteenth, illustrates another lesson: stability is not acceleration.

Kansas cleaned up its act a bit after years of fiscal whiplash and restored some predictability. Unemployment stayed relatively low. But job growth mostly tracked population growth. Why? One answer is that spending growth during surplus years offset gains from tax reform. Kansas fixed some leaks, but never fully opened the throttle.

South Carolina, ranked twenty-first, shows how local policy quietly shapes outcomes.

At the state level, labor markets are flexible and fiscal policy is moderate. But in many counties, local spending and property taxes rose faster than population and inflation, creating pockets of drag. The result is uneven growth — strong in some regions, sluggish in others. The entrepreneurs who direct capital notice these differences even when statewide averages look fine.

Then there are Louisiana and Michigan, ranked thirty-first and thirty-second, respectively. Their stories differ, but the outcomes rhyme.

Louisiana’s right-to-work status hasn’t overcome large government and high taxes. Michigan’s earlier reforms helped — until policy reversed. In both states, private-sector job growth lagged and output underperformed. When rules become less predictable, capital doesn’t protest. It leaves.

Importantly, the story is not uniformly negative. States such as Idaho, North Dakota, and North Carolina have combined spending restraint with durable tax and labor reforms and improved their rankings meaningfully over time. These states focused on consistency rather than one-time fixes. The payoff has been stronger job growth, rising incomes, and sustained in-migration.

Now contrast these with California, New York, and Matt’s home state of New Mexico, which sit at the bottom of the rankings. High spending. Steep and complex taxes. Rigid labor rules. The predictable response? Net domestic out-migration, slower private-sector growth, and weaker income gains — even as budgets swell.

These data reinforce the intuition that people move away from high costs and low flexibility. A common objection is that these rankings are backward-looking. That’s true — and that’s the point. Institutions don’t change outcomes instantly. The index reflects what policies actually produced, not what politicians promise next. Using 2023 data filters out press releases and captures lived reality.

Over time, the pattern is unmistakable. States that protect economic freedom experience higher incomes, stronger employment, greater mobility, and more resilience. Those states that erode it experience the opposite — usually with a lag that makes denial tempting.

From a classical-liberal perspective, none of this should be surprising. Economic freedom respects individual choice, local knowledge, and voluntary exchange. The fact that it also delivers better outcomes is not an accident. It is the market mechanism at work.

The political economy lesson is simple but uncomfortable: prosperity doesn’t come from doing more. It comes from consistently getting out of the way. Spending restraint, simple taxes, and flexible labor markets are not exciting. But they are effective.

The data keep saying the same thing. The states keep proving it. Economic freedom still wins — even when politics pretends otherwise.

(For comparison with and complement to the Fraser data, AIER’s Jason Sorens and Will Ruger compile the Freedom in the 50 States Index of Personal and Economic Freedoms.)