The longest federal shutdown in US history has created deep gaps in the flow of economic data, preventing calculation of the Business Conditions Monthly indices. Most BCM components depend on federal statistical agencies, including the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and the Federal Reserve, that were unable to collect, process, or publish October 2025 data. As a result, critical indicators such as payroll employment, labor force participation, consumer price index, industrial production, housing starts, retail sales, construction spending, business inventories, factory orders, personal income, and several Conference Board composites remain unavailable or were published without the sub-series needed for BCM methodology. Agencies have already confirmed that several October datasets were never collected and cannot be reconstructed. And while a handful of private and market-based measures (University of Michigan consumer expectations, FINRA margin balances, heavy truck sales, commercial paper yields, and yield-curve spreads) continued updating normally, the BCM cannot be produced unless all 24 components are available for the same month; missing even one Census or BLS series renders the entire month unusable.

Because the October data will not be produced, that month is permanently lost for BCM purposes. The indices can resume only once federal agencies complete their post-shutdown catch-up work and release full, internally consistent datasets for the next available month in which all 24 BCM components exist. Even once resumption begins, calculations based on the first complete month may reflect a gap that renders that initial reading economically suspect. Based on current release schedules, the earliest realistic timeframe for restoring the BCM is early 2026, once a complete set of post-shutdown data is again available.

This new data void is a graphic illustration of how short-term, error-prone, and erratic US economic policy has become, echoing earlier episodes such as the “transitory” miscalculation of 2021, the ruinous and clumsily-handled pandemic responses, and the panicked Fed rate hikes between 2022 and 2023 which resulted in a minor banking crisis.

Discussion, October – November 2025

September’s inflation data (released October 24th) offered a rare clean signal in an otherwise muddied environment, confirming a broad though modest cooling in both headline and core CPI before the federal shutdown froze statistical agencies. Headline CPI rose 0.31 percent and core 0.23 percent, both softer than expected, with year-over-year core easing to 3.0 percent. Goods inflation softened, helped by declining vehicle prices and deflation among low–tariff-exposure categories. Core services, meanwhile, slowed sharply on a sizable drop in shelter inflation. Firms continued to pass through roughly 26 cents of every dollar of tariff costs, leaving price pressures elevated but stable, and diffusion indices showed slightly narrower breadth, with fewer extreme increases or declines. Combined, these data reinforced market expectations for another rate cut in December.

Producer price data (released November 25th) painted a similar picture of contained underlying pressures, reinforcing the disinflationary tilt suggested by the CPI. September headline PPI firmed to 0.3 percent on an energy spike, but core PPI rose only 0.1 percent, below expectations, and categories feeding into the Fed’s preferred core PCE gauge were mixed. Portfolio-management fees fell sharply, medical services posted uneven readings, and airfares jumped, suggesting pockets of resilient discretionary spending. Overall producer-side inflation remained tame. Prices for steel and aluminum products covered by Section 232 tariffs have risen about 7.6 percent since March yet appear to be leveling off, supporting the observation that tariff-driven pressures are largely one-time rather than accelerating. The challenge ahead is that October CPI and several subsequent releases will be heavily compromised: two-thirds or more of price quotes were never collected during the shutdown, forcing the Bureau of Labor Statistics to rely on imputation well into spring 2026. As a result, September’s moderate inflation reading may be the last clean data point for months, complicating the Fed’s ability to gauge true disinflation progress even as markets continue to anticipate further easing.

Against this backdrop, the Fed entered its October 28–29 meeting with more uncertainty than usual and opted for the path of least resistance: cutting rates by 25 basis points and announcing that quantitative tightening via the balance sheet will be dialed back starting on December 1st, citing tightening liquidity conditions and a lack of reliable data as the shutdown froze much of the federal statistical system. Policymakers framed the cut as insurance against downside labor market risks even as Chair Powell used his press conference to push back against the idea that another cut at the December 9–10 meeting is guaranteed, emphasizing sharply divided views on the Committee, evidence that bank reserves are slipping from “abundant” to merely “ample,” and the need to pause without fresh official readings on employment or inflation. The statement’s sober description of growth as “moderate,” despite private-sector estimates nearer 4 percent, underscored how the absence of October CPI, payroll data, and other inputs are forcing the Fed to rely on partial and private data, much of which points to softening hiring but continued consumer spending. Markets initially assumed a follow-up cut in December, but Powell’s more hawkish tone, noting lingering inflation frustrations, mixed labor signals, and uncertainty about whether recent growth is real or overstated, pulled those odds down sharply. Investors are now bracing for a data-blind December decision in which alternative labor indicators may carry more weight than any official release.

This dynamic is sharpened by the fact that September’s nonfarm payrolls report is now the only official labor data point available to the Fed before the December meeting, complicating case for another rate cut at a time when the shutdown has halted JOLTS (next release: August 2025, on December 9th), ADP (October 2025, on December 3rd), and every other major labor indicator for October and November. Payrolls rose by 119,000, more than double the consensus, with gains concentrated in construction, health care, and leisure and hospitality. The prior two months were revised down, August job creation turned negative; the unemployment rate rose to 4.44 percent; the latter primarily because labor force participation jumped. Wage growth slowed to 0.2 percent, and sector-level data showed uneven hiring with services expanding, transportation and warehousing shrinking and unemployment inflows continuing to exceed outflows for a third month. In total, the report suggests gradual softening of labor market conditions beneath the surface.

With October and November employment reports cancelled and the next release tentatively planned for December 16, policymakers are left to make a December decision based on a single, stale release, private proxies, and fragmentary signals.

Meanwhile, October’s Institute for Supply Management surveys offered a split view of the underlying economy, reinforcing the sense that growth is uneven but still resilient in places. Services activity accelerated meaningfully, with the headline index rising on the back of strong new orders and renewed business activity — these were partially fueled by data center demand and a burst of mergers and acquisitions in tech and telecom. Contrarily, manufacturing slipped further into contraction at as production reversed sharply following September’s jump. Yet beneath the manufacturing headline, several forward-looking indicators improved, including new orders, backlogs, and employment, all alongside price pressures easing as producers reported input costs rising at a slower pace. Services told the opposite inflation story, with the prices-paid index surging to its highest reading since 2022 and respondents explicitly citing tariffs as a driver of higher contract costs even as service-sector employment contracted more slowly. Taken together the ISM data depict an economy still expanding on the services side while manufacturing remains weak but stabilizing, with demand firming across both sectors even as inflation dynamics sharply diverge.

Those mixed signals contrast with a sharp deterioration in household sentiment. Consumer sentiment fell in November 2025 to one of the lowest readings ever recorded as Americans reported the weakest views of their personal finances since 2009 and the worst buying conditions for big-ticket goods on record. Despite inflation expectations easing for both the one-year (4.5 percent) and long-term (3.4 percent) horizons, households remain deeply strained by high prices, eroding incomes, and growing job insecurity, with the probability of job loss rising to its highest level since mid-2020 and continuing unemployment claims climbing to a four-year high. The survey also highlighted a widening split between wealthier households (whose stock market gains and assets cushion them) and non-stockholders, whose financial positions are deteriorating even as headline economic data appear steady. Of particular note American consumer views darkened even after the federal shutdown ended, suggesting that sentiment is being driven less by political theater and more by lived economic pressure.

View on the other side of the cash register were not materially brighter, which reinforces the broader theme of a cooling but still functioning economy. Small business sentiment slipped to a six-month low in October with the National Federation of Independent Business optimism index falling as firms reported weaker earnings, softer sales, and rising input costs. Half of the index’s components declined, including a notable drop in owners’ expectations for future economic conditions – now at their lowest since April – while the share reporting stronger recent earnings posted its steepest decline since the Covid pandemic. Hiring challenges eased, with only 32 percent of respondents unable to fill openings and fewer firms citing a lack of qualified applicants. Yet near-term hiring plans ticked down for the first time since May, reflecting caution rather than confidence. Price pressures moderated, planned price hikes slipped to a net 30 percent, and somewhat paradoxically the uncertainty index fell to its lowest level of the year (yet remained high by historical standards). The consequent picture is one where firms are still uneasy, yet not panicking, about souring trends in demand, margins, and the broader economic trajectory.

In retail consumption the recent narrative is similar: signs of slowing momentum but not collapse. September brought a modest downshift from August’s brisk pace as households eased off goods purchases after an unusually strong back-to-school season, even as discretionary spending at restaurants and bars remained solid. Headline retail sales rose just 0.2 percent, with most of the softness concentrated in nonstore retail, autos, and the control group categories (clothing, sporting goods, hobby items, and online purchases) all of which gave back part of the summer’s surge. Food services and drinking places, by contrast, continued to post healthy gains, suggesting the pullback in goods was more a matter of normalization than retrenchment, and that spending momentum remained intact through the end of the third quarter. Despite the mixed monthly profile, strength earlier in the summer left real consumer spending on track for a robust 3.2 percent annualized gain in the third quarter, underscoring that households, however stretched and anxious, were still spending steadily heading into the shutdown.

All of this must be interpreted through the lens of the unprecedented disruption of the federal statistical system. The next industrial production and capacity utilization readings are likely to be released on December 3, but beyond that, the timing of most other releases remains uncertain, and agency leaders must now decide which October data can be reconstructed and on what schedule. The CPI presents the thorniest case: with two-thirds of its 100,000 monthly price quotes gathered through in-person store visits, none of which occurred in October 2025, the probability is high that no October CPI will ever be published, and the November CPI may also be delayed beyond the December FOMC meeting. Missing shelter data will complicate rent calculations well into the first quarter of 2026, while surveys fundamental to unemployment measurement simply cannot be recreated weeks after the fact. Although payroll employment and GDP are less vulnerable, because both can be backfilled from employer and business records, the broader effect is essentially the same: for the next several months, official US data will be patchy, delayed, and in some cases permanently incomplete.

Even once agencies resume full operations, the statistical damage will ripple outward, affecting not only headline indicators but also numerous dependent series and long-running supplements. The unemployment rate may post its first missing observation in more than 75 years, since labor market transition measures cannot be estimated. The education supplement to the October household survey will disappear entirely. More immediately, the delays in the November employment report and CPI mean the Fed’s December rate decision will be made with little to no official visibility on inflation or labor conditions for two full months — an extraordinarily rare and consequential impairment. While most of the record will eventually be repaired, the next several weeks will hinge on crucial judgments by BLS, BEA, Census Bureau, and Federal Reserve officials about accuracy, feasibility, and timing. Those choices will inexorably determine how quickly the economy’s statistical foundation regains its footing.

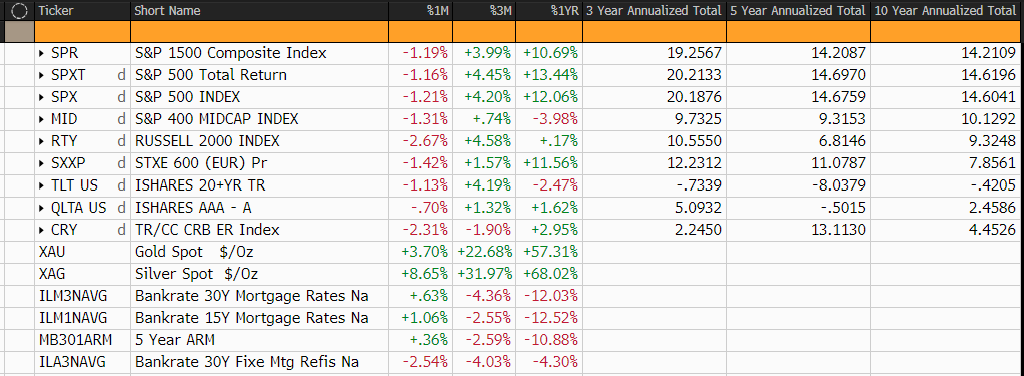

Back to the macroeconomic outlook: soft data show the economy’s split personality: services expanding while manufacturing contracts but stabilizes, consumer sentiment collapsing to near-record lows amid deteriorating personal finances and job anxiety with consumption remaining strong, and small-business optimism slipping on weaker earnings and softer sales. The loss of October and November’s core indicators, plus gaps going forward, mean that policymakers have no reliable read on inflation momentum or labor market cooling, forcing them to evaluate the economy through anecdotes and information patches rather than a full picture. In this environment, even modest surprises — whether in private-sector labor trackers, ISM reports, or high-frequency spending data — carry outsized weight, shaping market expectations and policy debates in ways that would never occur under normal statistical conditions. For now, the lone clear signal amid the noise is the price of gold, and its message is unmistakably cautious.